Framework for change

Erika Elkady laments the narrow ‘academic’ approach of modern education, but sees the potential of an ancient ideal to provide a framwork for change.

Education needs to change

We often hear that education needs to change and arguably the pandemic amplified this call even more. The 19th century model of teaching and learning has clearly not been working for quite some time. Unfortunately, the world of education is slow to adapt. The late Ken Robinson, but also others such as Tony Wagner already warned us over a decade ago that ‘things’ were not going well. Sadly, ‘things’ are only getting worse for many children. The mental health statistics of young adolescents become more worrisome each year and the percentage of school dropouts is still on the rise.

The focus in education is still on high stakes, often external, pen-and-paper exams. Academic results are too often the be all and end-all in school inspections when rating and ranking schools. Universities operate more or less along the same lines as transcripts which show only letters or numbers are often decisive in deciding to admit or reject students. As a result, the pressure is also on teachers and school leaders who feel they operate in a culture of limited opportunities for growth and development and where they have little to no autonomy. It is therefore no surprise that many demoralized educators are leaving the profession altogether.

Response to change

Whilst governments and universities are slow to respond to change, schools are trying to implement ‘wellbeing’ initiatives to support their students and staff. However, most of these well-intended activities are often ad hoc responses which lack academic research and rigor. For example, some schools are banning mobile phones thinking this will increase student focus and reduce social media addiction. Other schools change the school menu, offer mindfulness classes, and provide opportunities for students to be more physically active hoping this will all improve their mental and physical wellbeing.

Since we seem to have lost the raison d’être of education, it may be helpful to remind ourselves what the purpose of education used to be. From ancient times, one key philosophical idea has been that schools (and especially those in the Western world) equipped children with the intellectual toolbox to make the ‘right’ decisions enabling them to flourish as individuals and in society. In other words, the development of positive character traits (virtues) was the aim of education. Simply put, people who are able to cope with the ups and downs in life are able to live well and contribute positively to society. And isn’t this what the public and private sectors in most countries should want for their citizens?

Character Education

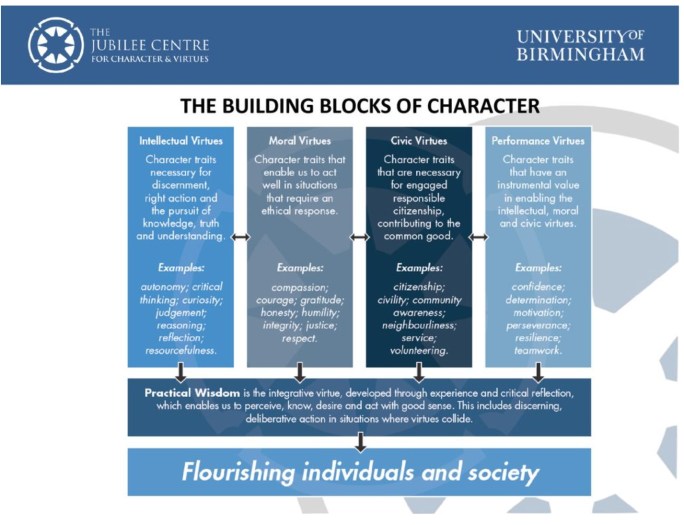

What was simply seen as good education in the past can be called “character education”, which in a nutshell promotes all activities inside and outside of school to help young people develop positive character strengths so they can live well as individuals and in society. The Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues at Birmingham University in the UK divides character strengths into four building blocks. The intellectual and performance virtues, although often not explicitly taught, receive the most emphasis in schools. However, in order to flourish, character development should be based on moral development. A neo-Aristotelian view of the psychology of moral development describes two pathways to virtuous action. Both pathways – an intrinsic and an extrinsic one – advocate the need to habituate virtues at home and in school.

An intentional, planned, organized and reflective character education program in a school should not be seen as extra work on the busy plates of teachers, but as the plate itself (Berkowitz). Almost all schools have a vision statement and although not all schools may live it, schools have their own ethos or ways to do things in the school. It is important to make these clear by defining and listing what values the school wants to prioritize and integrate in the teaching and learning in and out of school, so students learn the meanings and identify appropriate practices to apply these in their lives, respect themselves and be of service to others.

Charcter – caught, taught and sought

It is important that teachers in the school are role models whose character can be emulated by students. Teachers who, for example, are patient, compassionate and have high expectations will see that their students “catch” these virtues. Therefore, the ‘caught’ aspect of character education is crucial, making the recruitment of adults in the school -who wholeheartedly buy into the school’s vision, mission and values- a priority.

Another aspect of character education is ‘taught’; providing opportunities and making the character strengths explicit in teaching will help students obtain the language, knowledge, understanding, skills, and attributes that enable character development.

Finally, character education is also ‘sought’ by encouraging students to participate and initiate activities which allow them ‘to feel good by doing good’. It also increases student voice enabling students to make a positive impact on a local, national and global level. Volunteering, service learning, and community awareness come to mind.

Character education in an IB context

IB schools may see character education as an opportunity to consciously embed many aspects of the IB educational philosophy. The virtues listed in the building blocks of character are approaches to learning skills as well as the IB learner profile traits. The sought aspect of character education resonates with the IB’s emphasis on service learning. However, IB schools, and especially Diploma schools, also tend to overwork their students. Teaching the ATL skills explicitly, embedding the IB LP traits in the curriculum, and having an authentic and meaningful service-learning program may further empower students to feel well, be well and do well.

Erika Elkady has been working in leadership positions in IB schools for 25 years. She is an IBEN member and currently working as an independent educational consultant.

FEATURE IMAGE: by liravega from Pixabay

Support image: by John Hain from Pixabay

Bibliography:

Berkowitz, M.W. (2021b). Primed for Character Education. Six Design Principles for School Improvement. New York: Routledge.

Gleason, D. (2017). At What Cost? Defending Adolescent Development in Fiercely Competive Schools. Developmental Empathy LLC.

Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. (2017). A Framework for Character Education in Schools. Retrieved from A Framework for Character Education: https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/userfiles/jubileecentre/pdf/character-education/Framework%20for%20Character%20Education.pdf

Kristjánsson, K. (2015). Aristotelian Character Education. Oxon: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Loewus, L. (2021). Why Teachers Leave—or Don’t: A Look at the Numbers. Retrieved from Education Week: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/why-teachers-leave-or-dont-a-look-at-the-numbers/2021/05

Robinson, K. and Aronica, L. (2015). Creative Schools. The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education. New York: Viking.

Wagner, T. (2008). The Global Achievement Gap. Why Even Our Best Schools Don’t Teach the New Survival Skills Our Children Need – and What We Can Do About It. New York: Basic Books.