Applied History and sustainability

Roman Krznaric takes a new look at what it means to learn from the past and why this has become even more essential for all our futures.

Learning from the past

‘The principal and proper work of history being to instruct, and enable men, by the knowledge of actions past, to bear themselves prudently in the present and providently in the future.’ – Thomas Hobbes, 1628

In recent years there has been a growing trend amongst historians to recognise the virtues of Applied History. This is the idea that learning about the past is not just valuable for its own sake but that it can be put to use to help us better navigate the turbulence of our own times. It’s an old idea going back to writers such as Thucydides, Thomas Hobbes and Goethe. But as I argue in my new book, History for Tomorrow: Inspiration from the Past for the Future of Humanity, it is especially relevant today in the face of the global ecological crisis, where we are failing to draw on the inherited wisdom of past civilizations.

History and the circular economy

Just as crucially, searching the past to help us confront our current environmental dilemmas is a way of bringing history to life for students and making it feel utterly relevant and essential to understanding the world we live in. So what would it look like to bring Applied History into the classroom and curriculum?

Let’s start with a topic like the circular economy: the idea that we need to shift from the old industrial model where we take nature’s resources, turn them into products, use them for a while and then throw them away, to a no-waste regenerative system where we use material resources over and over again, constantly refurbishing, repairing, reusing and recycling. This topic might typically be tackled in geography or economics lessons. But history also offers unparalleled insights.

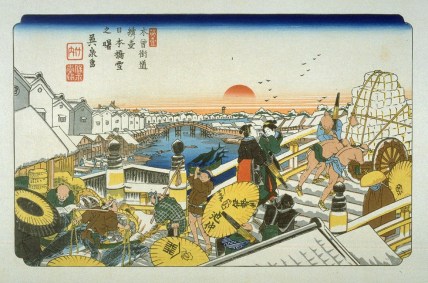

The circular economy of Edo Japan

Take, for instance, the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan. At the time, the capital city Edo (today’s Tokyo) had over one million inhabitants and effectively operated as a highly sustainable circular economy, partly due to resource scarcity brought about by the regime having cut international trade links. When your cotton kimono wore out, you might turn it into pyjamas, and then later cut it up to make nappies, then turn it into cleaning cloths, and finally burn it for heat. There were thousands of small businesses engaged in activities like repairing umbrellas and collecting candle wax to be reused. The regime also embarked on one of the world’s first mass plantation forestry schemes to replenish their depleted woodlands. Edo Japan has good claim to be the world’s first large-scale ecological civilisation and is an inspiration for creating more sustainable economies today. We’ve done it in the past, so what’s stopping us from doing it again?

Radical policy change and disruption

Another topic where history offers insight is how we tackle the climate crisis. It is clear that we need transformative public policies to stay below 1.5° of heating, but governments are not acting at the speed and scale required. If we look to history, it becomes evident that outside crisis periods such as wartime or pandemics, radical policy change is most likely to happen with the help of disruptive social movements.

Another topic where history offers insight is how we tackle the climate crisis. It is clear that we need transformative public policies to stay below 1.5° of heating, but governments are not acting at the speed and scale required. If we look to history, it becomes evident that outside crisis periods such as wartime or pandemics, radical policy change is most likely to happen with the help of disruptive social movements.

That’s the story of the slave uprising in Jamaica in 1831, which rapidly accelerated the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 in Britain. It’s the story of the Suffragettes who chained themselves to railings and went on hunger strikes, of the movement for Indian independence, and the campaign for US civil rights. Today’s ecological movements such as Extinction Rebellion or Fridays for Future are part of long traditions of effective popular resistance.

History and reimagining the future

I don’t believe that these kinds of examples should be brought into the classroom as illustrations of iron laws of history (there aren’t any: nothing in history is inevitable until it happens). Rather, their purpose is to open up the imagination to different ways of organising our societies and creating change. They can help us see beyond the myopia of the present or the belief that technological solutions will come to our rescue. As teaching tools, they also provide scope for critical discussions about issues such as the dangers of romanticising the past or the role of race and gender.

There is enormous – and largely untapped – scope for bringing history into play in the design of teaching around sustainability issues. Ecological literacy depends on our understanding of the past. In my ideal world, Applied History would be integrated into school curriculums in multiple subject areas, from history and geography to economics and civic education, drawing on learnings from some of the best university-level Applied History courses.

As we journey towards an uncertain future, let us etch into our minds the Māori proverb,

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua – “I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on the past.”

Roman Krznaric is a social philosopher whose books have been translated into over 25 languages. This article draws on his new book, History for Tomorrow: Inspiration from the Past for the Future of Humanity, which will be published in July 2024.

Roman Krznaric is a social philosopher whose books have been translated into over 25 languages. This article draws on his new book, History for Tomorrow: Inspiration from the Past for the Future of Humanity, which will be published in July 2024.

Roman is Senior Research Fellow at Oxford University’s Centre for Eudaimonia and Human Flourishing and founder of the world’s first Empathy Museum. He is a TCK and previously a student at Island School, Hong Kong.

Click on the book cover to follow the link to Amazon to pre-order.

Feature Image: by https://www.istockphoto.com/portfolio/MariaKorneeva?mediatype=photography

Support Images: Many thanks to Roman for providing the images.