Sustainability and school design

Award-winning architect Harry Hoodless reflects on working with schools in order to help them design the kind of sustanable school that is right for them.

Defining sustainability

For me, ‘sustainability’ is a catch-all word designed to help us form some sort of purpose with regard to environment, our place in society and its operational mechanisms. That’s huge!

All good architects will have an approach to sustainability and in my view, many will have great ideas that will be unique. This is not a bad thing given differentiation is key to great international school experiences.

The common ground in all sustainable approaches, no matter how different, however, is cost: perhaps 10-15% more capital expenditure will be required over a typical budget for school buildings. As long lifespan owner occupiers whose primary stakeholders are the very future of our society, international schools are the perfect client to push the needle. I urge you all to take the long view. The direction you push that needle is something quite exciting to explore.

“Why don’t you just put on a jumper?”

I moved to Shanghai in the summer of 2010 and I talked at an event about the work I had just done in the UK, building colleges to high performance standards and measuring operational carbon emissions for the first time. In the Q&A a man started shouting. When translated it became clear he was accusing me of creating waste, damaging landscapes, and building buildings for westerners who like walking around in their underwear in the winter. In China, he said, people put a jumper on. This comment stuck with me, as I reflected on my post grad research, which was about the roots of modern environmentalism and design.

The sustainable design spectrum

There are two extreme views about humanity’s place in our planet’s ecosystem. As post-industrialised citizens we have become accustomed to advanced technology and the comfort this wealth of ingenuity has provided. We have been able to extract huge amounts of energy and resources from the planet, which to many has become a standard. The extreme techno-centric view is that any problem humanity must face can be solved through invention. Climate emergency problems can be mitigated, or we just adapt. It’s an optimistic position.

Nexus International School (Singapore)

A progressive education environment with an optimistic and technology-focused position on environmentalism, led by Harry Hoodless for Broadway Malyan.

At the other extreme, an eco-centric view believes humanity is an infestation, with just a few people responsible for out stretching our planets resources and leaving many with little to support their wellbeing in now hostile ecological environments. Their answer is the radical dethroning of humans from a natural order, giving up technology as we know it and living more pre-industrial lives. Of course, this requires a huge reduction in human population, perhaps a step back in time. This is in some respects optimistic as well: ‘deep ecologists’ dream of a better future too.

Ecocentric soft technology in architecture, Green School, Bali

You can then consider the spectrum of approaches between these extreme views, apply a little technology to the eco-centric view so earth can support more people in harmony with the species that support them. Or perhaps one might manage the extreme technocentric view through environmental regulation (this is how most of us in the global north and developed regions of the world live).

Different approaches for different schools

All these views could be considered to entail ‘environmentalism’ and I don’t believe there is a right or wrong in any of them, but my clients should be aware of the range of views and form their own perspective as part of a design process.

The work I do helps by breaking sustainability into manageable chunks and focusing on understanding. We talk about a school’s values, the mission statements on your website, and what they might mean. We talk about experiences within a school, prompt and listen as your character emerges and after this, we consider a position on environmentalism that works for you. I feel this approach will key environmentalism into a school community and be accepted long term, or in other words, be sustainable.

Only then can we start to develop a brief to define material, mass, form, structure, technology, pattern, texture, tone and ecology in tandem with a detailed experience design, unique to you.

Greenhouse at Dulwich College Singapore: environmentally managed spaces for education, with evidence and data analytics undertaken as part of the design work by DP Architects and DP Sustainability.

I’d urge those looking at developments not to leap at the application of renewable technologies as the saviour, but determine your position on environmentalism first, and get to the root of what might work for you. The dialogue might be a great way to bring the school community together, raise awareness and have something to measure against.

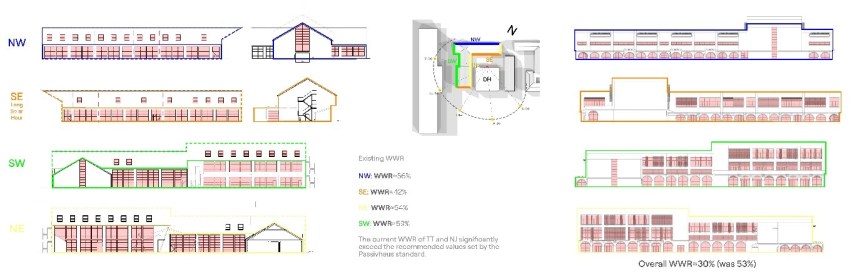

Window wall ratio analysis as part of a building retrofit study, confidential school project by Kampus / Studio Hoodless, Europe.

Sustainability payback

The business case for sustainable schools can look complex, with risks outweighing returns. In their 2002 book Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, architect William McDonough and chemist Michael Braungart use cherry blossom as an analogy for the merits of eco-effectiveness over efficiency. Natural systems pay back in ways that nourish a complex range of interdependencies. For schools, the students are your cherry blossoms and by instilling a value proposition that is ‘felt’ within their school experience, they spill out into society in a very effective way.

Discuss the sustainability brief

The crux of this is in an architectural conversation about the things we all know, but perhaps we don’t ask about or express. As a minimum, does your development brief include sustainability as a topic with metrics or detail?

I’ve written design guides for a few large school groups and sustainability references broad management tools that can be efficient. Although we now need to look at the numbers about energy, ecology and carbon more carefully, we also need to ensure the intent is actioned. If it is in the brief and not discussed further, that’s greenwash, and our future generations will come back to judge us. I recommend taking the students with you on an estates journey in a positive way. When they talk as adults, that’s a long-term business model and inherently sustainable.

Most developers, operators, and educators we work with are grappling with the word sustainability. It’s huge and complex and to think we can ‘solve’ all these interdependencies could be considered arrogant, so I urge you not to worry, and start step by step.

Harry Hoodless is the founder and director of Studio Hoodless. Having lived and worked internationally, designing and delivering a range of projects from large masterplans to single buildings and interiors, he now advises on environmental design strategy and implementation.

Harry Hoodless is the founder and director of Studio Hoodless. Having lived and worked internationally, designing and delivering a range of projects from large masterplans to single buildings and interiors, he now advises on environmental design strategy and implementation.

He is the Education Architect at Kampus.

FEATURE IMAGE: Confidential school project by Kampus / Studio Hoodless, Europe. If your values are Caring, Courageous, Ethical, Global, Curious, Resilient, and Respectful what would your dining building experience be?

All images kindly provided by Harry.