The Importance of Building Reading Fluency in Every Classroom

To comprehend and discuss challenge-level text, English learners (ELs) must first be able to read the content relatively fluently. Fluency in reading is the ability to read print material with accurate decoding, appropriate pacing, and prosody. Prosody— that is, meaningful expression—involves suitable rhythm, intonation, stresses, and pauses for the text. To read aloud at an efficient pace, with good expression, an EL must capably break a text sentence into meaningful syntactic and semantic units. In other words, reading emotively partly hinges on a student’s recognition of key grammatical features and logical phrases.

Fluency serves as a critical conduit between decoding and comprehension. When students can read a text passage with efficient decoding, effective pacing, and meaningful expression, they are able to free up brain power to focus on the actual text content. Because students acquiring English approach standards-aligned prose with gaps in language knowledge, they cannot be expected to achieve fluency and grasp text meaning after only one reading. Whether a teacher reads aloud or groups peers for a shared read-aloud, one pass at a demanding text section is woefully insufficient.

In all subject areas, teachers must structure multiple reads of an assigned text, one section at a time, and provide effective models of fluent reading to support all basic readers, ELs and English speakers alike. Advanced narrative and informational texts are not designed for a single riveting read-aloud, spontaneous auditory processing, and immediate discussion of the key idea and details. To illustrate, a sixth-grade science chapter on the causes of seasons contains complicated sentence structures, a heavy concept load, and unfamiliar academic vocabulary that strain a listener’s short-term memory. Similarly, the Newbery Medal–winning novel Number the Stars focuses on forced relocation of Jews in Denmark during World War II. Even with a relatable eleven-year-old protagonist, this work of historical fiction merits conscientious rereading and guided analysis of key passages for middle school readers to grasp geographic, political, social, and thematic nuances.

Visual 1

Text Reading

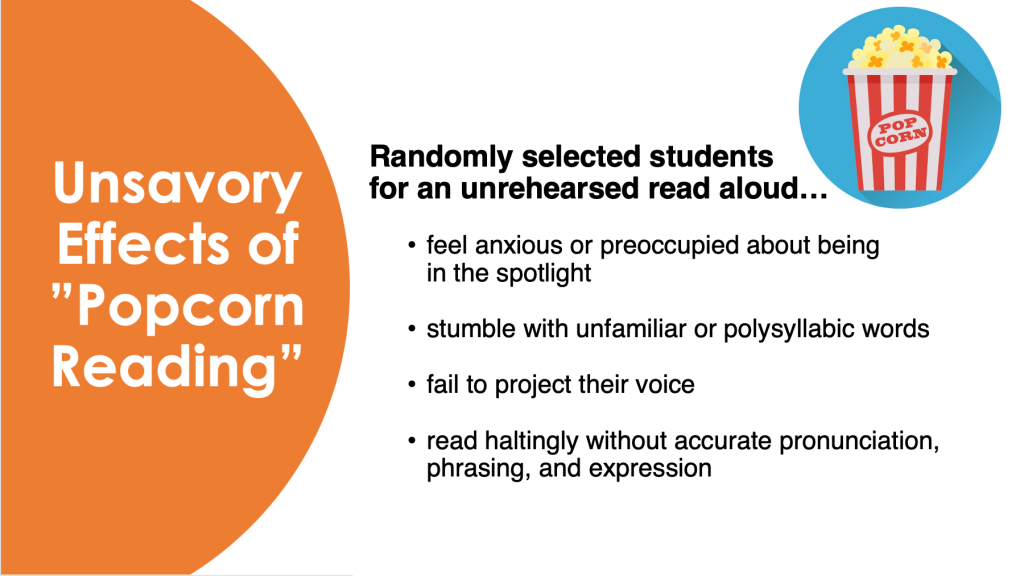

Faced with a complex unit text, an unforgiving pacing plan, and basic readers striving to access meaning in a second language, many teachers resort to the “popcorn reading” strategy they experienced firsthand in their own formative schooling. The name popcorn reading derives from the practice of spontaneously calling on students to read aloud a short passage, whether their hands are raised or not. The process customarily begins with the teacher leading the charge and reading aloud the first text section.

Next, the teacher popcorns—that is, rapidly appoints the initial student reader, at times randomly with a name card or digital device. The unsuspecting victim is charged by the teacher with a cold unrehearsed reading of unfamiliar text in front of peers. As the reader stumbles inaudibly through polysyllabic words and complicated sentence structures, classmates typically dodge eye contact or are preoccupied anticipating what might be the next assigned passage. The teacher routinely intervenes to correct pronunciation as the reader falters, enhancing performance anxiety and further sabotaging fluency. The exhausted reader ultimately concludes, breathes a sigh of relief, turns over the reins to a nominated peer, and disengages.

This ineffectual classroom practice may be anticipated and forgiven in the hands of a substitute teacher outside of their curricular element and going rogue on a provided lesson plan. Unfortunately, veteran and novice teachers alike resort to it routinely when poorly equipped with more productive strategies to support developing readers in tackling challenging text. This instructional mainstay fails to build reading fluency and comprehension because students are not reading text sections multiple times, nor are they reliably benefitting from fluent, audible reading models. Of equal concern, only one individual, either the teacher or the designated student reader, is engaged in actual reading, while most classmates sit passively listening, anxiety-ridden, skipping ahead, or distractedly awaiting their turn. Moreover, pivoting to text-dependent questions after a single read-aloud, a teacher signals to neophyte readers that successful “reading to learn” is an elusive and innate talent, like a beautiful singing voice, rather than a competency developed through multiple purposeful reads (see Visual 2).

Another unproductive practice in upper-elementary and secondary coursework is to assign students to small groups to take turns reading aloud segments of a focal unit text. Whether referred to as round robin reading or collaborative reading, this strategy can readily backfire. Under the guise of peer-assisted learning, readers with varied levels of proficiency and confidence attempt an unrehearsed reading of their segment while fellow group members often sit idle, worried, or actively off task. As a teacher educator regularly coaching read” to “It’s not my turn” to “I am the motivator.”

Like the ubiquitous popcorn reading strategy, round robin group reading does not achieve the intended outcome of text engagement and comprehension because students do not have an active and accountable role as a peer reads aloud, nor are they profiting from repeated reading and effective fluency models. Both classroom staples have no defensible research base and thus merit being discarded in the instructional dustbin.

Visual 2

Establishing Schoolwide Fluency Routines

Extensive research has identified repeated reading as the key strategy for improving students’ fluency skills (NICHD, 2000). Repeated reading incorporates two essential elements: 1) giving students the opportunity to read and then reread the same text passage, and 2) having students practice reading orally with teacher guidance provided as needed. ELs most definitely benefit from planned and consistent teacher guidance with reading lesson material, from text passages to directions to model verbal and written responses. Any challenge-level content should be read multiple times, using familiar instructional routines. An instructional routine is a “research-informed, classroom-tested, step-by-step sequence of teacher and student actions that are regularly followed to address a specific instructional goal“ (Kinsella, 2018). Rather than a revolving door of activities and indefensible strategies like popcorn reading, English learners depend upon their teachers for classroom practices that will advance their text understanding and literacy skills. Adopting a set of consistent schoolwide fluency routines improves student text engagement and confidence because vulnerable readers are familiar with the processes and poised to focus on learning.

The Building Fluency Routines outlined below provide a model of capable reading with a clearly communicated, active, and accountable student role. They progress in a gradual release model from “I do” (teacher-mediated) to “We do” (teacher and class) to “You’ll do” (peer-mediated) to “You do” (independent). Students who actively participate in teacher-mediated reading of text gain the fluency they need for subsequent partner and independent text rereading and response. Although many basic readers are quite content to sit back and listen as a teacher or proficient classmate reads aloud, passive listening will not improve reading fluency or comprehension. The phrase-cued “echo” reading routine (Glavach, 2011; Kinsella, 2017) and the oral cloze routine (Harmon and Wood, 2010; Kinsella, 2017) can be effectively implemented across upper-elementary and secondary subject areas to promote learner engagement and reading fluency.

Visual 3

Effective Building Fluency Routines

Before introducing students to one or more of the Building Fluency Routines, it is important to explain what reading fluency is and describe the characteristics of fluent readers (see Visual 1). Teachers in every subject area must provide a compelling rationale for multiple reads of a challenge-level text, detailed task directions, or writing assignment exemplars.

We can lessen their reading anxiety by emphasizing that we will make every effort to help them read course material more comfortably and capably. It is helpful to clarify what you perceive as the challenge level of something you are expecting them to read because lesson material isn’t static in terms of complexity.

Within core content coursework, I have found it useful to display a color temperature scale to visually demonstrate the level of text complexity in our lesson content and justify the amount of segment rereading we will do before text marking and discussion.

First Read—Tracked Reading: The teacher reads aloud a text segment while students look carefully at the words and silently track, following with their finger, pencil, cursor, or guide card (a colored five- by eight-inch index card).

1. Explain the Task: Direct students to look carefully at the words as you read aloud at a “just right pace,” not too fast or slow, and to use their finger, pencil, cursor, or guide card to track the text and silently follow along.

2. Read Aloud: Read aloud each sentence at a moderate rate, with enhanced expression, pausing at natural intervals while students silently track.

Second Read—Echo Reading: The teacher reads aloud a text segment, breaking each sentence into meaningful phrases, cueing students to look carefully at the words and “echo back,” imitating the teacher’s capable pronunciation, emphasis, and pausing. When introducing the routine, consider typing a text excerpt and inserting slash marks to illustrate for students the meaningful phrasing and where you will pause to cue students to echo back (see Visual 3).

1. Explain the Task: Direct students to look carefully at the words as you read a phrase aloud, then echo back, imitating your pronunciation, emphasis, and pausing.

2. Read Aloud: Read aloud the target sentences within the text segment with enhanced expression, and pause at natural intervals, enabling students to chorally repeat the phrase. Repeat the process, combining key phrases so students are echo-reading lengthier phrasings. When introducing the routine, use a familiar hand gesture such as an open palm to cue repetition.

Third Read—Oral Cloze Reading: The teacher reads aloud a text segment, omitting a few carefully selected strong word choices within different sentences, while students follow along silently and chime in chorally with the missing words.

1. Explain the Task: Direct students to follow along silently as you read each sentence aloud and to chime in with the words you omit. Emphasize that you will only omit a few words, one at the beginning, middle, and end of the text segment, and that you will choose strong words (vs. prepositions, articles, etc.) you know they can pronounce.

2. Read Aloud: Read aloud at a moderate rate with enhanced expression, leaving out a few pre-taught or familiar words that come at the end of a meaningful phrase, each within a different sentence. Pause briefly for students to respond chorally after you omit a word. If some students do not chime in, or if they struggle with pronunciation of a word, clearly restate the word, and repeat the sentence to get students back on track. Repeat the process as needed, picking up the pace slightly and omitting different words.

Fourth Read—Partner Cloze Reading: Students read a text segment in three ways: 1) reading silently to choose words to omit while reading to their partner; 2) reading aloud to partner, omitting a few words; 3) following along reading and chiming in with words their partner omits.

1. Explain the Task: Tell students that they will read a manageable text segment aloud and leave out words for their partner to chime in, just as the teacher has done for an earlier read of the same material.

2. Facilitate the Process: Assign A/B partners and tell students which paragraphs or sentences within a paragraph they are responsible for reading aloud. Direct students to reread their assigned segment twice before choosing two or three words to omit when reading aloud. Advise students to choose meaningful nouns and verbs that come at the end of phrases. Encourage students to pick up their books and project their voices as they read aloud so their partners can easily follow.

When to Use Building Fluency Routines

English learners benefit from teacher-mediated reading support during many lesson phases. They deserve conscientious instructional attention to building reading fluency and comprehension well beyond text reading. Within dedicated English language development, intensive reading intervention, and core content classes, teachers can make excellent use of the routines (see Visual 4).

For example, to ensure more active participation in lesson discussions, teachers should clearly display prompts and follow at least a two-read protocol, with echo reading followed by cloze reading. I generally follow a three-read protocol whenever supporting newcomers and beginners: first, tracked reading; second, echo reading; third, cloze reading.

This sets the stage for clarifying a few key words in the prompt that may prove problematic for English learners and classmates who are basic readers. A two- to three-read protocol is equally essential when preparing English learners with response scaffolds. Response frames and model contributions should be visibly displayed and echo-read multiple times to build fluency, rehearsal, and confidence in contributing to the subsequent lesson interaction.

Visual 4

Concluding Thoughts

Persistently low national literacy rates demand an informed and sustained commitment from schools and districts to adopt practices that are in our students’ best interests. ELs require robust oral language and English language development in tandem with explicit reading and writing instruction. The Building Fluency Routines I have introduced have a proven track record of improving student engagement and literacy in linguistically diverse classrooms while not requiring reading intervention certification to effectively execute. I encourage you to introduce these practices in your next PLC or staff meeting and make a schoolwide commitment to implement them with consistency and fidelity. Your colleagues will feel like they have added potent yet practical tools to their instructional toolkit, and their students will have much to gain.

References

Glavach, M. J. (2011). “The Brain, Prosody, and Reading Fluency.” National Association of Special Education Teachers, The Practical Teacher.

Harmon, J., and Wood, K. (2010). “Variations on Round Robin Reading.” Middle Ground, 14(2).

Kinsella, K. (2018). “Are Strategies Helpful or Harmful for Teachers and English Learners?” Language Magazine.

Kinsella, K. (2020). English 3D: Language Launch, Vol. 1. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Kinsella, K. (2017). English 3D: Course A–C. Teaching Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. NICHD. (2000). National Reading Panel Report.

Kate Kinsella, EdD ([email protected]), writes ELD curriculum and provides consultancy and professional development throughout the US addressing evidence-based practices to advance English language and literacy skills for multilingual learners. She is the author of research-informed curricular anchors for K–12 English learners, including English 3D, Language Launch, and the Academic Vocabulary Toolkit.